Is the Medical Establishment Sabotaging the Fight Against Chronic Infections?

What the latest research and mounting clinical evidence indicates

By Harold Fickett and Dr. Robert Malone

In 2016 a San Antonio police officer named Robert Taylor began to experience what’s politely termed “pelvic pain.” Generally, this manifests as stabbing and burning sensations overlaid by a relentless, crushing pressure. In less clinical terms, it’s like a boa constrictor squeezing your genitals while simultaneously digesting them with its stomach acids.

San Antonio police officer Robert Taylor

Taylor recalls the experience as “hell on earth.” Much worse than the pain he felt when he was stabbed on duty.

Soon after the onset of the pain, he couldn’t work or sleep.

He sought help immediately from a urologist. The doctor told Taylor he probably had a case of Chronic Bacterial Prostatitis (CBP).

There was good news, though, as CBP is readily treatable. The doctor performed a rectal exam, took tissue samples, prescribed the standard antibiotics for CBP, and sent the specimens out for testing. He told Taylor that he ought to feel much better in about ten days. In the meantime, he also prescribed pain medications.

Taylor saw no improvement in ten days and received little relief from the pain medications. His physician reported that his test results came back negative or “within scope.” He would prescribe a broader-spectrum antibiotic.

Why hadn’t the test results revealed anything?

That often happened, the urologist admitted, even when there were clearly pathogens present. The testing had its limits. By prescribing a broader-spectrum antibiotic, his physician was resorting to the “empirical method.” Since traditional cultures fail so often to provide any diagnostic information, physicians prescribe antibiotics that have worked in the past to cure patients with similar symptoms. The “empirical method” boils down to making educated guesses.

As Taylor’s condition persisted, his life began to fall apart. The pain became all-consuming, leaving him withdrawn and self-absorbed. He began to worry about his sanity.

He tried a second urologist, then a third, then a fourth. Each performed the same rectal exam, wrote a prescription for one or more antibiotics, and assured him he ought to start feeling better soon.

This went on for two years. One day the fourth urologist, clearly exasperated by the lack of results, suggested that Taylor seek help from a psychiatrist, if only to improve his coping resources. Too tired to argue, Taylor simply left and never returned.

Now at his physical, emotional, and spiritual nadir, Taylor broke down one night and confessed to his wife that he was thinking of killing himself. He couldn’t bear the suffering, or the burden that suffering was putting on others.

Dr. Timothy Hlavinka

That’s when he found out about Dr. Timothy Hlavinka.

Dr. Hlavinka, a urologist with an international clientele, seemed able to help people like Taylor, whose conditions only puzzled and frustrated other physicians. Taylor made an appointment. Hlavinka’s first recommendation had to do with diagnosis. The Culture and Sensitivities (C&S) testing his other doctors had run had long been the standard but had a 40% to 70% failure rate for Robert’s condition. Accuracy was actually slightly worse now that the process was automated, the only change in this technology since the Civil War era.

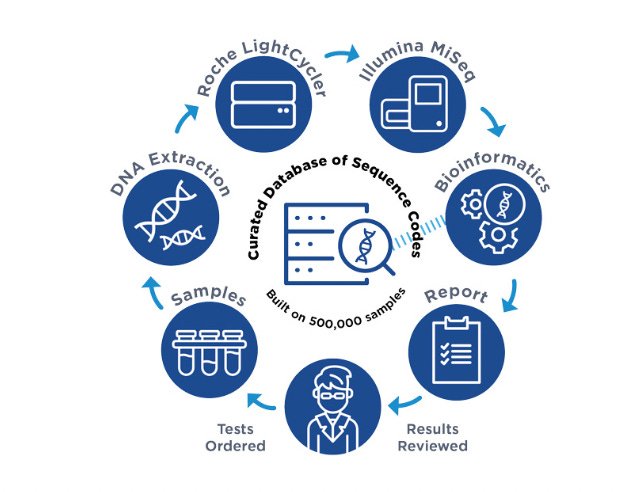

Nucleic acid extraction (NGS)

Dr. Hlavinka wanted to have Taylor tested by the Lubbock, Texas lab of a company called MicroGenDX (MicroGen Diagnostics). They use a process called Nucleic acid extraction, which is based on running a DNA analysis of all the bacteria and fungi found in the specimen. The results would allow Dr. Hlavinka to prescribe more targeted antibiotics.

This made perfect sense to Taylor. DNA analysis had been used in law enforcement for thirty years. Why hadn’t this been done before?

Taylor submitted urine samples (MicroGenDX’s testing can also use other common samples like blood, saliva, semen, and skin) and was told to expect an initial report within as little as twenty-four hours, followed by a full report in three to five days.

For the full report, MicroGenDX employed both qPCR and well as an advanced sequencing technology involving next-generation deep sequencing for nucleic acid extraction (NGS). This produces results that can be compared against the company’s proprietary database of over 57,000 bacteria and fungi, including genetic variations.

The full report ranks the relative “load” of each microbe as “low,” “medium,” or “high,” with an approximation of the DNA copies per gram. It also indicates the relative percentage of a given bacterium or fungus. This helps the physician distinguish between disease causing bacteria and commensals, which exist in benign symbiosis with the body. It also provides a more extensive record of the drug resistant genes present, while recommending antibiotics for effective treatment

Taylor’s first MicroGenDX test showed four organisms. The primary bacteria were Acinetobacter wolfia and E. coli, both undoubtedly pathogenic. The latter two, Massilia timonae and Finegoldia magna, were rare. Their role in Taylor’s condition would have to be determined through further analysis.

Dr. Hlavinka mainly knew they were in for a fight, since polymicrobial infections—infections in which two or more bacteria participate—can present mystifying challenges. But even this limited information left him with more informed treatment options than were available to Taylor’s previous urologists

Polymicrobial infections are frequently referred to as “biofilms.” This indicates the bonding of bacteria into a matrix that includes products from our bodies' attempts to thwart the infection. The bacteria not only cooperate but hijack the body’s protective measures to maintain their collective toxicity.

Another way to portray polymicrobtial infections are as “colonies” that operate under a “calyx” or umbrella-like structure. Although the metaphor is inexact, we might imagine a polymicrobial infection as a nasty, exploitative off-planet mining colony with several types of workers operating under a protective dome.

The governance of the colony might also be compared to organized crime, with direction supplied by its dominant strains. Polymicrobial colonies even have their own form of “omerta,” or vow of silence. Bacteria have an uncanny ability to hide from detection.

Many of the ways in which bacteria keep hidden are not yet understood. A few discoveries have been made in this regard, however. For example, bacteria can hide in white blood cells, the very agents the body sends to attack them, often multiplying until they explode the cells apart in a kind of toxic storm. They can also hide within the cell walls of the organs they are infecting.

Such was the tenacious and elusive foe that had attached itself to the wall of Robert Taylor’s prostate, systematically stripping him of the will to live.

Taylor’s treatment extended over four different courses of antibiotics. Each was directed against the dominant strains of bacteria that showed up in a succession of MicroGenDX tests.

This did not surprise Dr. Hlavinka. Delay in proper diagnosis of a chronic infection allows polymicrobial colonies to become stronger and stronger, with more survival tactics at their disposal. Each course of antibiotics brought others out of hiding until the entire colony was obliterated. Taylor made a full recovery.

Dr. Hlavinka sees this as proof that extensive biofilms are behind the suffering of hard-to-treat patients like Taylor. “Nothing else explains the ‘treat one and another pops up’ phenomenon,” he says. And he has no doubt that he could never have helped Taylor using only traditional culture and the “empirical method.” Taylor, now thriving both at home and at work, agrees.

“This is life-changing technology,” he says. “It kept me around for my wife and kids.”

DNA testing may have been used for decades in criminology—and every Forensic Files episode, but the U.S. medical establishment has resisted adopting its diagnostic use for bacterial and fungal infections for years. The insurance companies, hospital networks, doctors’ associations, and medical journals that guide conversations about the field show an unwillingness to replace C&S with NGS.

This despite the widely-accepted accuracy of NGS and the emergence of an industry eager to implement it. In addition to MicroGenDX, the Mayo Clinic and the University of Washington also offer NGS, if on a more limited basis and at greater cost. Then there’s Karius, an NGS service that works with blood samples. Even PCR-only services like BioSphere and Pathogensis offer a measure of improvement over C&S alone. NGS testing services can also be ordered directly from MicroGenDX.

For patients like Taylor, the resistance to NGS is puzzling, if not infuriating. It also has larger ramifications for public health. Misdiagnosed infections result in ineffective antibiotic prescriptions. This in turn contributes to the evolution of “super bugs,” whose susceptibility to even the most advanced antibiotics is rapidly diminishing. According to The Lancet, 1.2 million people in 2019 died across 204 countries from anti-microbial resistance (AMR)—people administered antibiotics that proved ineffective. The rate of death from AMR outpaced mortality from HIV/AIDS or malaria.

The Cavalry is not on the way.

Nor is help from new antibiotics on the way. As the headline of a recent Wall Street Journal article declares, “The World Needs New Antibiotics. The Problem Is, No One Can Make Them Profitably. New Drugs to defeat ‘superbug’ bacteria aren’t reaching patients.”

Two major sources of resistance to NGS adoption are Labcorp and Quest, the dominant players in the seven-billion-dollar-a-year US diagnostic testing market. Both companies have “leakage” provisions in their contracts which penalize customers who send out too high a percentage of specimens to competing laboratories.

There’s also medical skepticism. Some worry that sensitive detection of microorganisms [from molecular testing] could be associated with increased diagnostic confusion and dilemmas. This could lead to over diagnosis and associated over-treatment.

The Guidelines for 2022 (Recurrent Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women: AUA/CUA/SUFU Guideline by the American Urological Association still recommends traditional methods of testing. This Guideline has been widely used by private insurance companies to deny coverage for NGS testing by classifying it as “investigational/experimental,” even after the American Medical Association (AMA) and The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) accepted the use of MicroGenDX testing as “medically necessary” in 2019.

The medical profession is at a time of transition between a clearly outmoded diagnostic testing technology and molecular testing that relies on a greater knowledge base.

The benefits of NGS testing outweigh the risks, provided that it is interpreted with appropriate prudence.

Orthopedic applications

Dr. Javad Parvizi is a world-renowned expert in orthopedic infections who’s performed over 10,000 hip and knee replacements as well as their “revisions,” or secondary surgeries where part or all of the hardware implanted has failed.

An outcome-based study Parvizi and colleagues recently published in Clinical Infectious Diseases claims that NGS improves antibiotic stewardship through providing far more accurate results.

Before knee or hip replacement surgery, antibiotics are administered prophylactically to prevent post-surgical periprosthetic (prosthesis-related) infections. Parvizi asserts that in his experience in 30% to 40% of patients traditional testing fails to provide guidance for the administration of these antibiotics. The subsequent “blind” treatment greatly increased the risk of post-operative infections and promoted the over-prescription of antibiotics.

A new paper from Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology by Kaipeng Jia, Shiwang Huang, et. al. echoes this conclusion:

“mNGS has shown significant advantages over traditional culture, particularly in the context of mixed infections and UTIs that are difficult to diagnose and treat. It helps to improve the detection of pathogens, guide changes in treatment strategies, and is an effective complement to urine culture.”

Would physicians who do not practice in such advanced research facilities enjoy similar success? This question troubled Tucson-based infectious disease specialist Dr. Clifford Martin. He was especially worried that the siloed nature of medicine actively encourages over-prescription of drugs across narrow specialties.

After successfully treating chronic UTIs and prosthetic joint infections with NGS, Dr. Martin’s concerns changed focus. Dr. Martin says:

“Infectious disease doctors who understand the molecular testing and the nuances of making diagnoses based on ambiguous information should really be championing the appropriate use of it. They should be rolling it out widely in areas where patients are truly suffering or where there's diagnostic difficulty. The technology wasn’t the problem. The problem was educating our colleagues on what it is and how to use it appropriately.”

Hlavinka agrees. He keeps an informal tally of how many doctors each of his patients has seen prior to him, and how many traditional cultures they’ve had run. The current record is twenty- three doctors and fifty-four traditional cultures. One can only imagine how many rounds of antibiotics this amounts to.

“They need to vent.”

According to Hlavinka, the relief his patients feel is often accompanied by another emotion: anger. When they hear that he’s been using MicroGenDx’s NGS testing for more than six years they can’t help but rage at the suffering they could have avoided.

The key question is why aren’t these advanced sophisticated molecular diagnostic methods being used more widely? The most benign explanation is inadequate physician education. Once again, the health care delivery system is failing patients, who are being forced to take matters into their own hands by directly contacting companies, academic institutions, and informed physicians that provide these services.